- Home

- Taxonomy

- Term

- June

Engineered biocatalyst for making "drop-in" biofuels

28 June 2024

- Pratibha Gopalakrishna

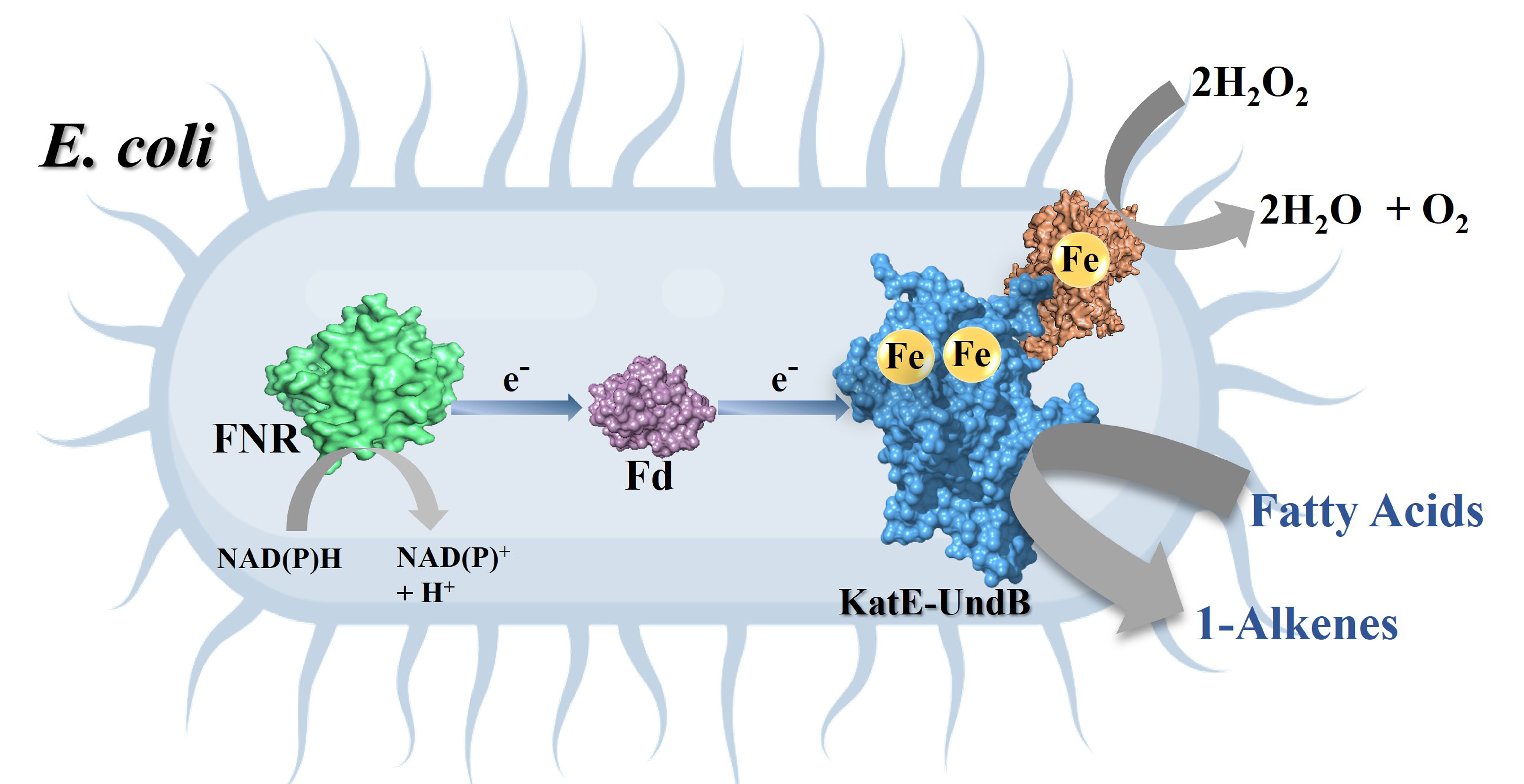

Researchers at the Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry (IPC), Indian Institute of Science (IISc), have developed an enzymatic platform that can efficiently transform naturally abundant and inexpensive fatty acids to valuable hydrocarbons called 1-alkenes, which are promising biofuels.

Given the finite availability and polluting nature of fossil fuels, scientists are increasingly exploring sustainable fuel pathways that involve compounds called hydrocarbons. They show great potential as “drop-in” biofuels, which can be blended and used with existing fuels and infrastructure. These hydrocarbons can potentially be synthesised on a large scale using microorganism “factories”. Enzymes that help mass-produce these hydrocarbons are therefore highly sought after. Hydrocarbons are also widely used in polymer, detergent and lubricant industries.

In a previous study, the IISc team purified and characterised an enzyme called UndB, bound to the membranes of living cells, especially certain bacteria. It can convert fatty acids to 1-alkenes at the fastest rate currently possible. But the team found that the process was not very efficient – the enzyme would become inactivated after just a few cycles. When they investigated further, they realised that H2O2 – a byproduct of the reaction process – was inhibiting UndB.

In the current study published in Science Advances, the team circumvented this challenge by adding another enzyme called catalase to the reaction mix. “The catalase degrades the H2O2 that is produced,” explains Tabish Iqbal, first author of the study and PhD student at IPC. Adding catalase, he says, enhanced the activity of the enzyme 19-fold, from 14 to 265 turnovers (turnover indicates the number of active cycles an enzyme completes before getting inactivated).

Engineered whole cell biocatalyst for efficient 1-alkene production (Image: Tabish Iqbal)

Excited by this finding, the team decided to create an artificial fusion protein combining UndB with catalase, by introducing a fused genetic code via carriers called plasmids into E. coli bacteria. Given the right conditions, these E. coli would then act as a “whole cell biocatalyst”, converting fatty acids and churning out alkenes.

However, there were several challenges. Being a membrane protein, UndB is extremely challenging to work with. Beyond a certain concentration, it can be toxic to bacterial cells. Membrane proteins like UndB are also not soluble in water, making it hard to maintain the right conditions for studying them.

To improve the efficiency of their chimeric protein, the team tested the effect of various “redox partner” proteins that help shuttle electrons to UndB during the conversion of fatty acids to alkenes. They found that proteins called ferredoxin and ferredoxin reductase, along with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), were able to supply electrons most efficiently. On incorporating these in the genetically modified E. coli and feeding fatty acids, the efficiency of conversion rose up to 95%.

A key advantage of this biocatalyst is that UndB is very specific and does not produce any unwanted side products – pure 1-alkene is the only product, says Debasis Das, Assistant Professor at IPC and corresponding author. “1-alkenes can directly be used as biofuels,” he adds.

From left to right: Subhashini Murugan, Debasis Das, Tabish Iqbal (Photo: Jayaprakash K)

The team found that their biocatalyst could convert a wide range of fatty acids containing different types of carbon chains to 1-alkene. They also showed that the biocatalyst can produce styrene, an important commodity in chemical and polymer industries.

The team has applied for a patent for their engineered protein and whole cell biocatalyst. They are also looking for industry collaborators to scale up the platform for mass-production.

“Our platform can be efficiently used to generate a large number of 1-alkenes that are valuable in biotechnology and polymer industries,” says Das.

REFERENCE:

Iqbal T, Murugan S, Das D, A chimeric membrane enzyme and an engineered whole-cell biocatalyst for efficient 1-alkene production, Science Advances (2024).

CONTACT:

Debasis Das

Assistant Professor

Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry (IPC)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: debasisdas@iisc.ac.in

Phone: +91 80 2293 3002

Website: https://sites.google.com/view/ddlaboratory/home

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

Turning infrared light visible

20 June 2024

- Ullas

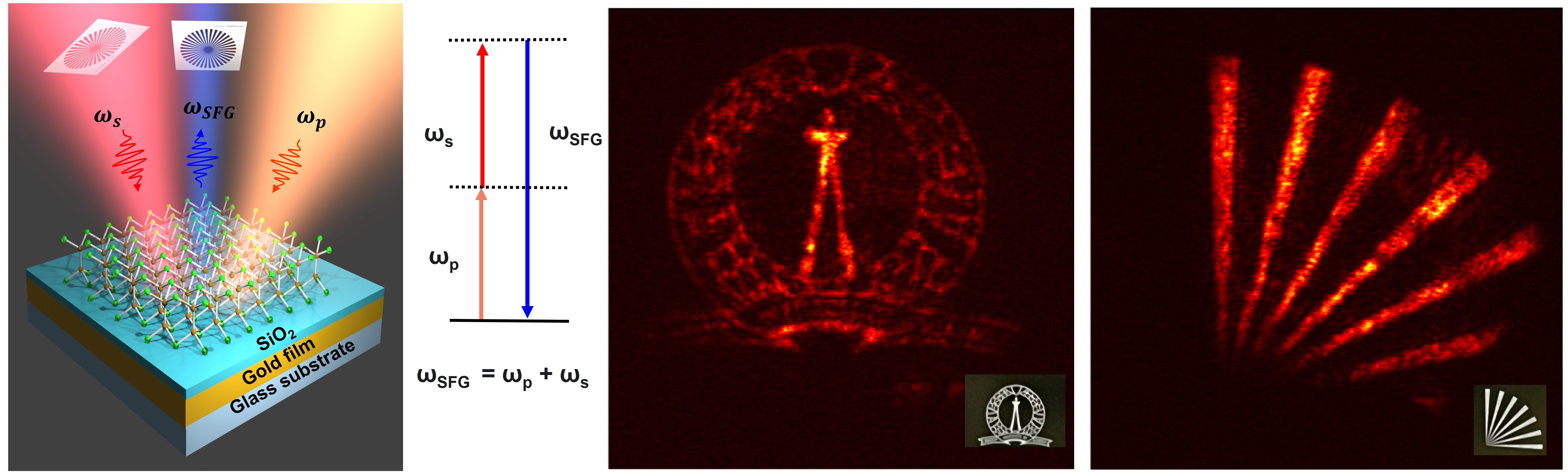

From Left to Right: Schematic of the nonlinear optical mirror used for up-conversion imaging. Energy diagram showing the sum frequency generation process used for up-conversion. Representative up-converted images of IISc logo and spokes where the object pattern at 1550 nm is upconverted to 622 nm wavelength (Images: Jyothsna KM)

The human eye can only see light at certain frequencies (called the visible spectrum), the lowest of which constitutes red light. Infrared light, which we can’t see, has an even lower frequency than red light. Researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) have now fabricated a device to increase or “up-convert” the frequency of short infrared light to the visible range.

Up-conversion of light has diverse applications, especially in defence and optical communications. In a first, the IISc team used a 2D material to design what they call a non-linear optical mirror stack to achieve this up-conversion, combined with widefield imaging capability. The stack consists of multilayered gallium selenide fixed to the top of a gold reflective surface, with a silicon dioxide layer sandwiched in between.

Traditional infrared imaging uses exotic low-energy bandgap semiconductors or micro-bolometer arrays, which usually pick up heat or absorption signatures from the object being studied. Infrared imaging and sensing is useful in diverse areas, from astronomy to chemistry. For example, when infrared light is passed through a gas, sensing how the light changes can help scientists tease out specific properties of the gas. Such sensing is not always possible using visible light.

However, existing infrared sensors are bulky and not very efficient. They are also export-restricted because of their utility in defence. There is, therefore, a critical need to develop indigenous and efficient devices.

The method used by the IISc team involves feeding an input infrared signal along with a pump beam onto the mirror stack. The nonlinear optical properties of the material constituting the stack result in a mixing of the frequencies, leading to an output beam of increased (up-converted) frequency, but with the rest of the properties intact. Using this method, they were able to up-convert infrared light of wavelength around 1550 nm to 622 nm visible light. The output light wave can be detected using traditional silicon-based cameras.

“This process is coherent – the properties of the input beam are preserved at the output. This means that if one imprints a particular pattern in the input infrared frequency, it automatically gets transferred to the new output frequency,” explains Varun Raghunathan, Associate Professor in the Department of Electrical Communication Engineering (ECE) and corresponding author of the study published in Laser & Photonics Reviews.

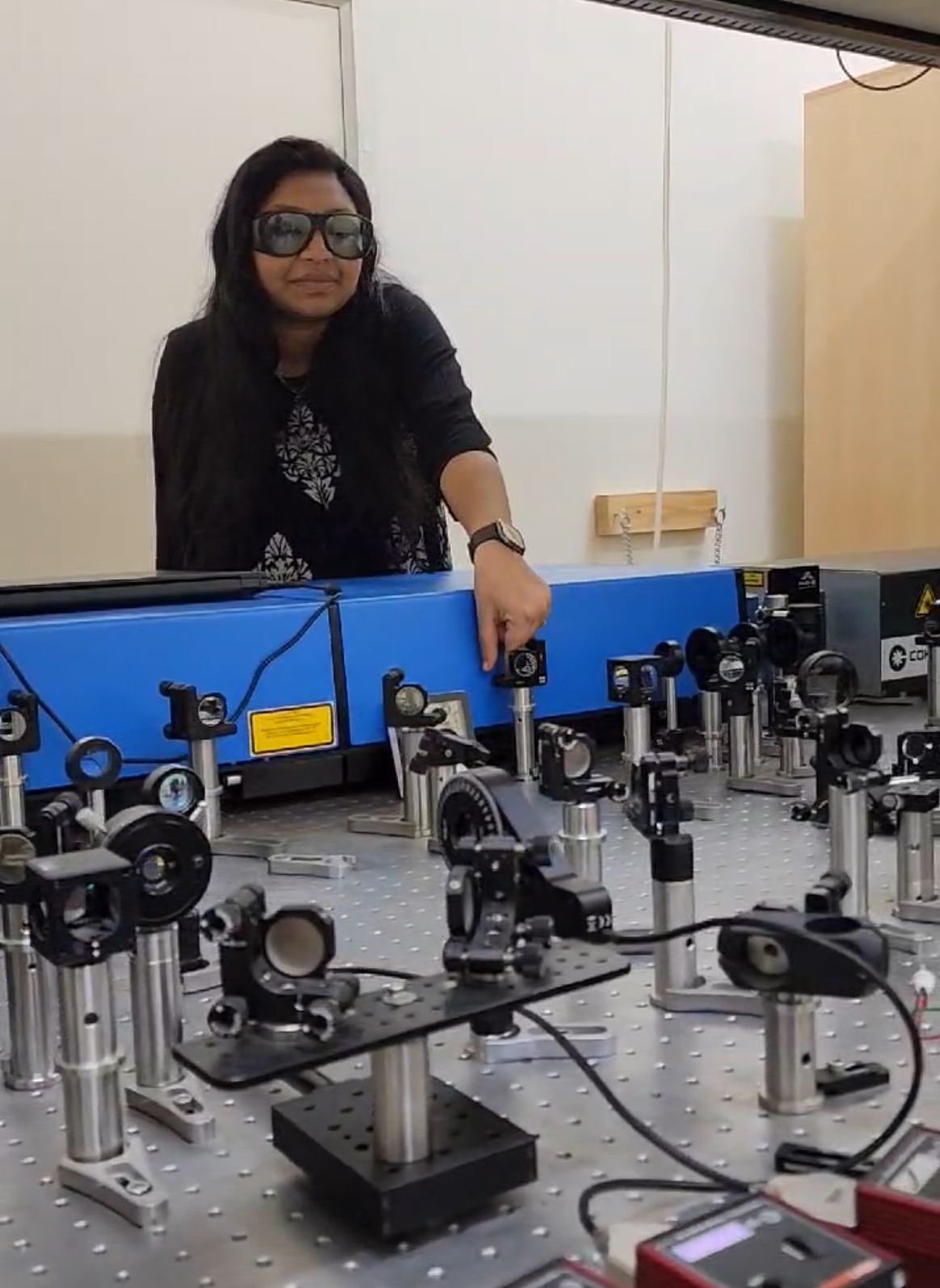

Lead author Jyothsna KM aligning optical beams for up-conversion experiments (Photo: Harinee Natarajan)

The advantage of using gallium selenide, he adds, is its high optical nonlinearity, which means that a single photon of infrared light and a single photon of the pump beam could combine to give a single photon of light with up-converted frequency. The team was able to achieve the up-conversion even with a thin layer of gallium selenide measuring just 45 nm. The small size makes it more cost-effective than traditional devices that use centimetre-sized crystals. Its performance was also found to be comparable to current state-of-the-art up-conversion imaging systems.

Jyothsna K Manattayil, PhD student at ECE and first author, explains that they used a particle swarm optimisation algorithm to speed up the calculation of the right thickness of layers needed. Depending on the thickness, the wavelengths that can pass through gallium selenide and get up-converted will vary. This means that the material thickness needs to be tweaked depending on the application. “In our experiments, we have used infrared light of 1550 nm and a pump beam of 1040 nm. But that doesn’t mean that it won’t work for other wavelengths,” she says. “We saw that the performance didn’t drop for a wide range of infrared wavelengths, from 1400 nm to 1700 nm.”

Going forward, the researchers plan to extend their work to up-convert light of longer wavelengths. They are also trying to improve the efficiency of the device by exploring other stack geometries.

“There is a lot of interest worldwide in doing infrared imaging without using infrared sensors. Our work could be a gamechanger for those applications,” says Raghunathan.

REFERENCE:

Manattayil JK, Lal Krishna AS, Asish Prosad A, Bag U, Biswas R, Raghunathan V, 2D Material Based Nonlinear Optical Mirror for Widefield Up-Conversion Imaging from Near Infrared to Visible Wavelengths, Laser & Photonics Reviews (2024).

CONTACT:

Varun Raghunathan

Associate Professor

Department of Electrical Communication Engineering (ECE)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: varunr@iisc.ac.in

Phone: +91-80-2293-3473

Website: https://sites.google.com/site/varunr196/home

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

Sustainable removal of heavy metal contaminants from groundwater

11 June 2024

- Sandeep Menon

The adsorbent stage (left) and remediation stage (right) in the pilot system in the lab (Photo courtesy: S3 lab, CST, IISc)

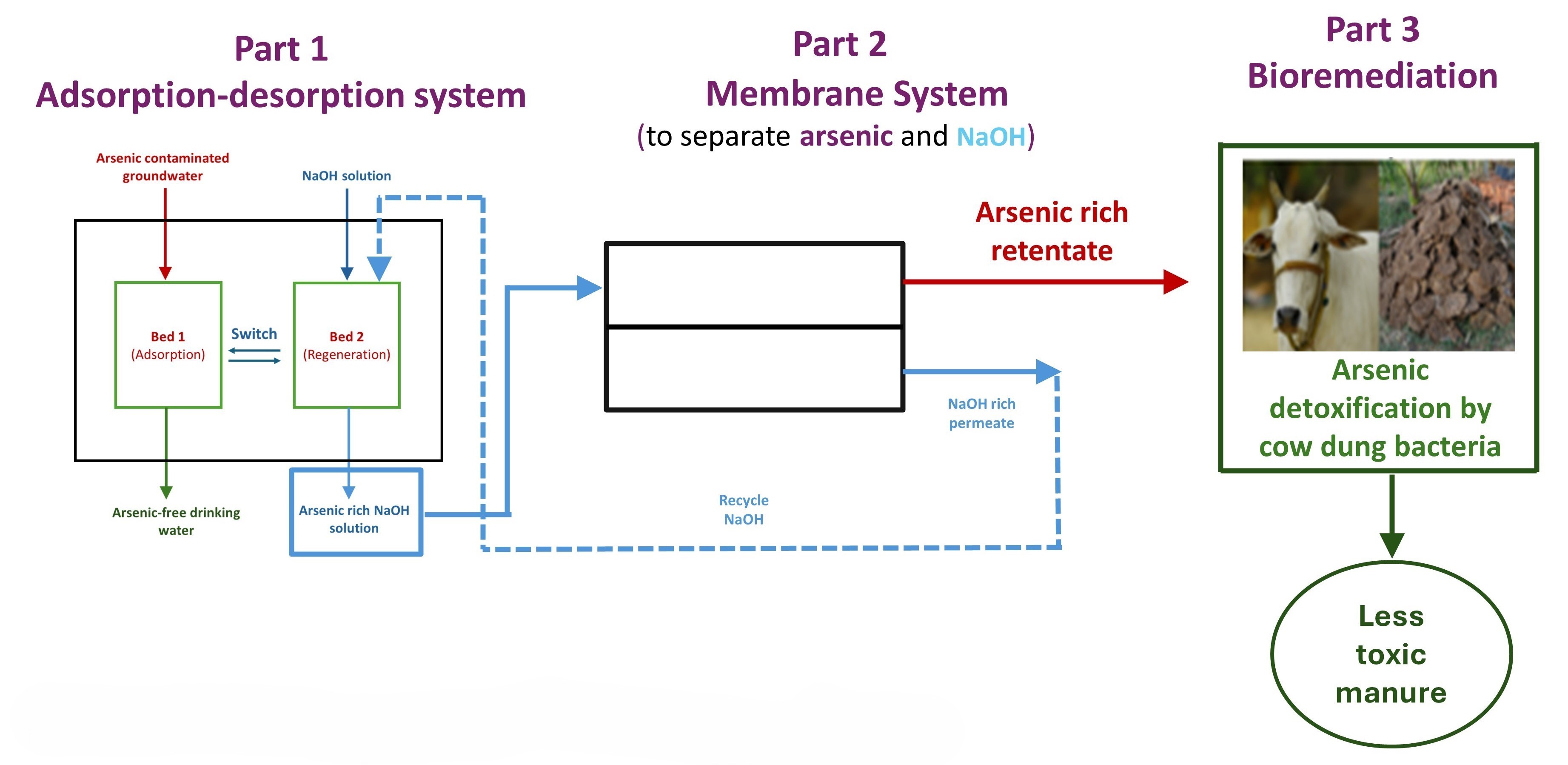

Researchers at the Centre for Sustainable Technologies (CST), Indian Institute of Science (IISc) have developed a novel remediation process for removing heavy metal contaminants such as arsenic from groundwater. The three-step method, which is patent-pending, also ensures that the removed heavy metals are disposed of in an environment-friendly and sustainable manner, instead of sending untreated heavy metal-rich sludge to landfills from where they can potentially re-enter groundwater.

“In every technology that exists, you can take out arsenic and provide clean water. However, after you remove the arsenic, you must do something about it so that it doesn’t re-enter the environment, and that aspect is not given due consideration in existing methods. Our process was designed to solve this problem,” says Yagnaseni Roy, Assistant Professor at CST, whose lab has developed the method.

According to reports, 113 districts in 21 states in India have arsenic levels above 0.01 mg per litre while 223 districts in 23 states have fluoride levels above 1.5 mg per litre, which are beyond the permissible limits set by the Bureau of Indian Standards and the World Health Organisation (WHO). These contaminants can significantly affect human and animal health, necessitating their efficient removal and safe disposal.

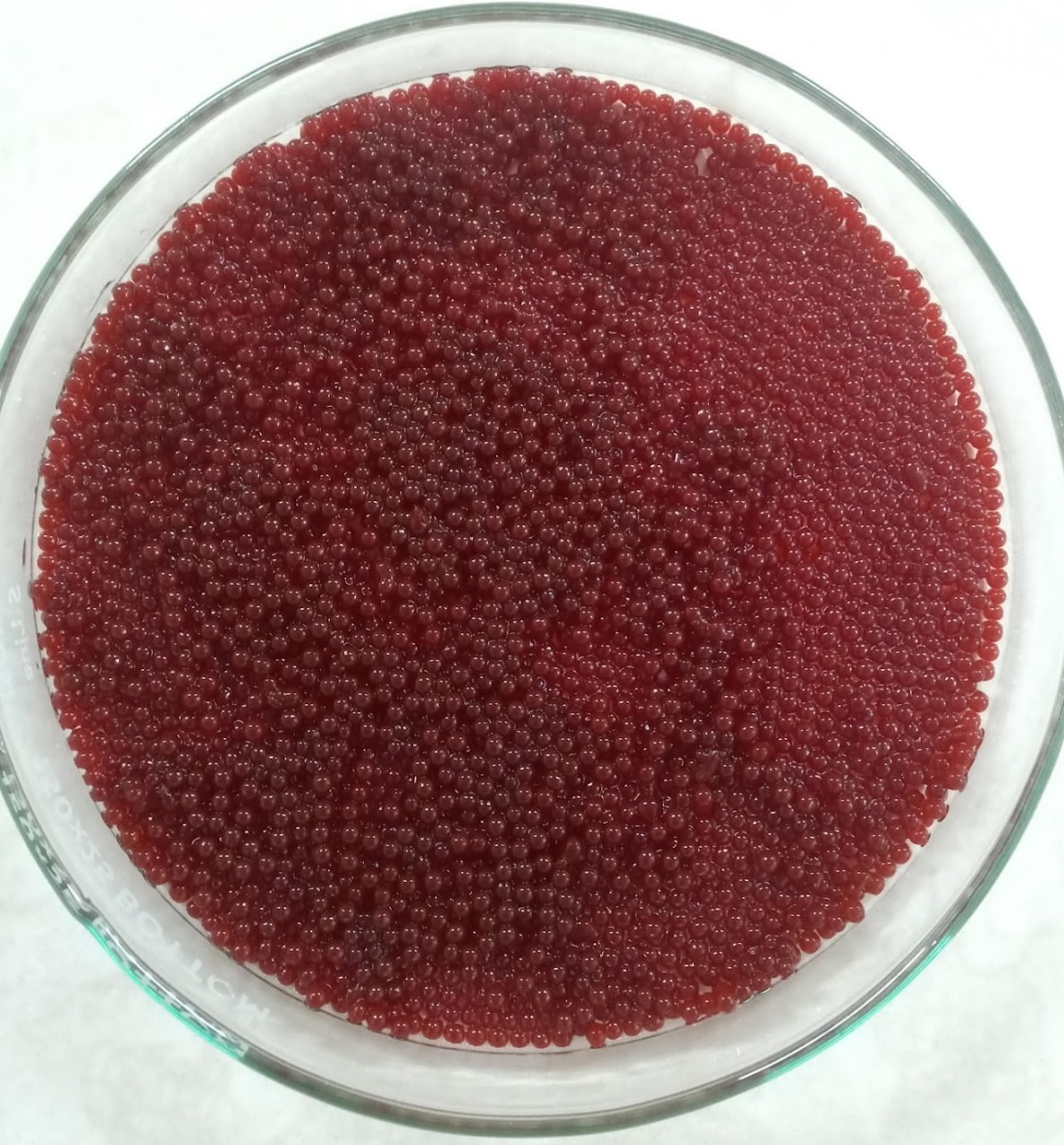

The first step in the process developed by the IISc team involves passing the contaminated water through a bed of biodegradable adsorbent made of chitosan – a fibrous substance obtained from crustaceans – doped with bimetallic (Fe and Al) hydroxide/oxyhydroxide. The adsorbent bed grabs the toxic inorganic arsenic through electrostatic forces and complex formation between arsenic and the adsorbent. A novel aspect of the technology is that the alkaline wash – used to repeatedly regenerate the adsorbent bed after its saturation – is recycled within the scheme.

Close-up view of the adsorbent beads (Photo courtesy: S3 lab, CST, IISc)

In the second step, the alkaline wash solution, which is essentially sodium hydroxide and arsenic in water, is taken to a membrane system to separate the two. While the sodium hydroxide solution (the alkaline wash) is taken back to regenerate the bed, the arsenic concentrated in the other stream is now ready to be taken to the third step: bioremediation. The membrane process serves to concentrate the arsenic ahead of bioremediation.

In the bioremediation step, the toxic inorganic arsenic is converted to low-toxicity organic arsenic via methylation by microbes found in cow dung. This results in a decrease of toxic inorganic arsenic to below the maximum permissible limit specified by WHO standards, within a span of eight days. The remaining cow dung sludge can be safely disposed of in landfills, since the arsenic is locked in it in an organic form.

"On average, these organic species are approximately 50 times less toxic than the inorganic form present in groundwater,” says Roy.

The system can also be adapted to remove fluoride, with the last step changed to precipitation to form calcium fluoride, which has very low solubility in water. Roy’s team is currently checking the feasibility of tackling other heavy metals using the same system.

Schematic of the process (Image courtesy: S3 lab, CST, IISc)

The system is easy to assemble and operate. Manufacturing the adsorbent material involves a simple recipe. In the lab, a small pilot-scale adsorption column system was able to generate safe drinking water (by WHO standards) for two people for three days. The researchers have been working with INREM Foundation and Earthwatch, both NGOs, to deploy and test these systems in rural areas such as Bhagalpur in Bihar and Chikkaballapur in Karnataka.

According to the researchers, such a system would work best at the community level.

“The collection of waste, maintenance and operation are easier on a community scale than individual houses. The maintenance is simple enough that it can be operated by people in the community itself, which will help with income generation for people operating the system,” says Rasmi Mohan T, PhD student at CST who has worked on the process. “For a larger scale, we might need funding to take it to various parts of the country.”

Along with Roy and Mohan, Master’s student Subhash Kumar and post-doctoral fellow Manamohan Tripathy have also been involved in developing the scheme at both lab and pilot scales.

CONTACT:

Yagnaseni Roy

Assistant Professor

Centre for Sustainable Technologies (CST)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: yroy@iisc.ac.in

Phone: 080 2293 3016

Website: https://www.s3iisc.com/home

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

Novel 3D hydrogel culture to study TB infection and treatment

25 June 2024

- Pratibha Gopalakrishna

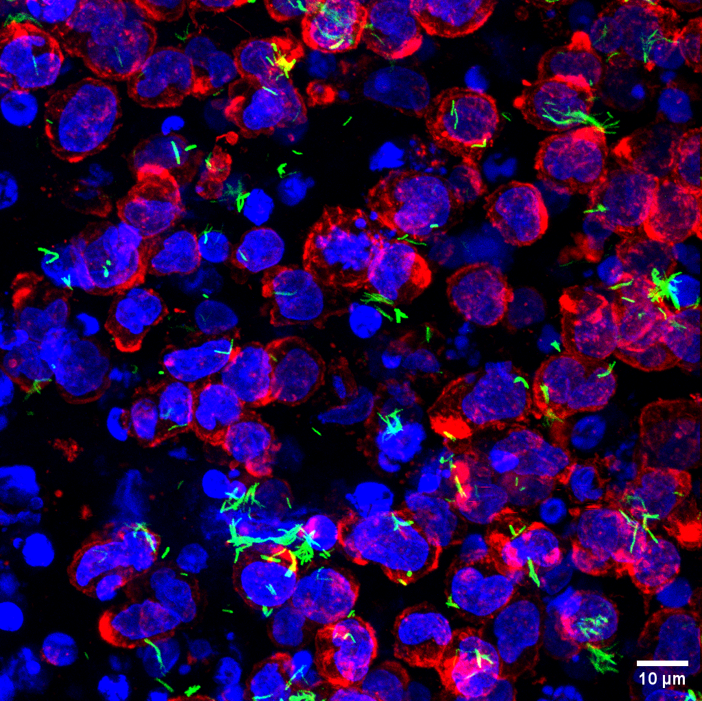

Human immune cells (nucleus: blue, cell boundary: red) with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (green) in the collagen hydrogels (Image: Vijaya V Vaishnavi)

Researchers from the Department of Bioengineering (BE), Indian Institute of Science (IISc), have designed a novel 3D hydrogel culture system that mimics the mammalian lung environment. It provides a powerful platform to track and study how tuberculosis bacteria infect lung cells and test the efficacy of therapeutics used to treat TB.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is a dangerous pathogen. In 2022, it affected 10.6 million people and caused 1.3 million deaths, according to the WHO. “It is a very old bug, and it has evolved with us quite a bit,” says Rachit Agarwal, Associate Professor at BE and corresponding author of the study published in Advanced Healthcare Materials. Mtb primarily infects the lungs.

Current culture models used to study Mtb infection have several limitations. They are typically culture plates that are monolayered and do not accurately mimic the 3D microenvironment inside the lungs. The microenvironment experienced by the cells in such 2D culture is vastly different from the actual extracellular matrix (ECM) surrounding lung tissue. “In a tissue culture plate, there are no ECM molecules, and even if a very thin layer of ECM is coated on these plates, the lung cells 'see' the ECM on one side at best,” explains Vishal Gupta, PhD student at BE and first author.

The 2D culture plates are also extremely hard compared to the soft lung tissues. “You are looking at a rock versus a pillow,” explains Agarwal.

He and his team have now designed a novel 3D hydrogel culture made of collagen, a key molecule present in the ECM of lung cells. Collagen is soluble in water at a slightly acidic pH. As the pH is increased, the collagen forms fibrils which cross-link to form a gel-like 3D structure. At the time of gelling, the researchers added human macrophages – immune cells involved in fighting infection – along with Mtb. This entrapped both the macrophages and the bacteria in the collagen and allowed the researchers to track how the bacteria infect the macrophages.

Vijaya V Vaishnavi (left) and Vishal K Gupta (right), lead authors of the study (Photo: Bhagyashree Padhan)

The team tracked how the infection progressed over 2-3 weeks. What was surprising was that the mammalian cells stayed viable for three weeks in the hydrogel – current cultures are only able to sustain them for 4-7 days. “This makes it more attractive because Mtb is a very slow-growing pathogen inside the body,” says Agarwal.

Next, the researchers carried out RNA sequencing of the lung cells that grew in the hydrogel, and found that they were more similar to actual human samples, compared to those in traditional culture systems.

The team also tested the effect of pyrazinamide – one of the four most common drugs given to TB patients. They found that even a small amount (10 µg/ml) of the drug was quite effective in clearing out Mtb in the hydrogel culture. Previously, scientists have had to use large doses of the drug – much higher compared to concentrations achieved in patients – to show that it is effective in tissue culture. “Nobody has shown that this drug works in clinically relevant doses in any culture systems … Our setup reinforces the fact that the 3D hydrogel mimics the infection better,” explains Agarwal.

Agarwal adds that they have already filed an Indian patent for their 3D culture, which can be scaled up by industries and used for drug testing and discovery. “The idea was to keep it quite simple so that other researchers can replicate this,” he adds.

Moving forward, the researchers plan to mimic granulomas – clusters of infected white blood cells – in their 3D hydrogel culture to explore why some people have latent TB, while others show aggressive symptoms. Gupta says that the team is also interested in understanding the mechanism of action of pyrazinamide, which may help discover new drugs that are more or just as efficient.

REFERENCE:

Gupta VK, Vaishnavi VV, Arrieta-Ortiz ML, Abhirami PS, Jyothsna KM, Jeyasankar S, Raghunathan V, Baliga NS, Agarwal R, 3D Hydrogel Culture System Recapitulates Key Tuberculosis Phenotypes and Demonstrates Pyrazinamide Efficacy, Advanced Healthcare Materials (2024).

https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202304299

CONTACT:

Rachit Agarwal

Associate Professor

Department of Bioengineering (BE)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: rachit@iisc.ac.in

Phone: +91-80-2293-3626

Website: https://be.iisc.ac.in/~rachit/

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

IISc physicists find a new way to represent ‘pi’

18 June 2024

While investigating how string theory can be used to explain certain physical phenomena, scientists at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) have stumbled upon on a new series representation for the irrational number pi. It provides an easier way to extract pi from calculations involved in deciphering processes like the quantum scattering of high-energy particles.

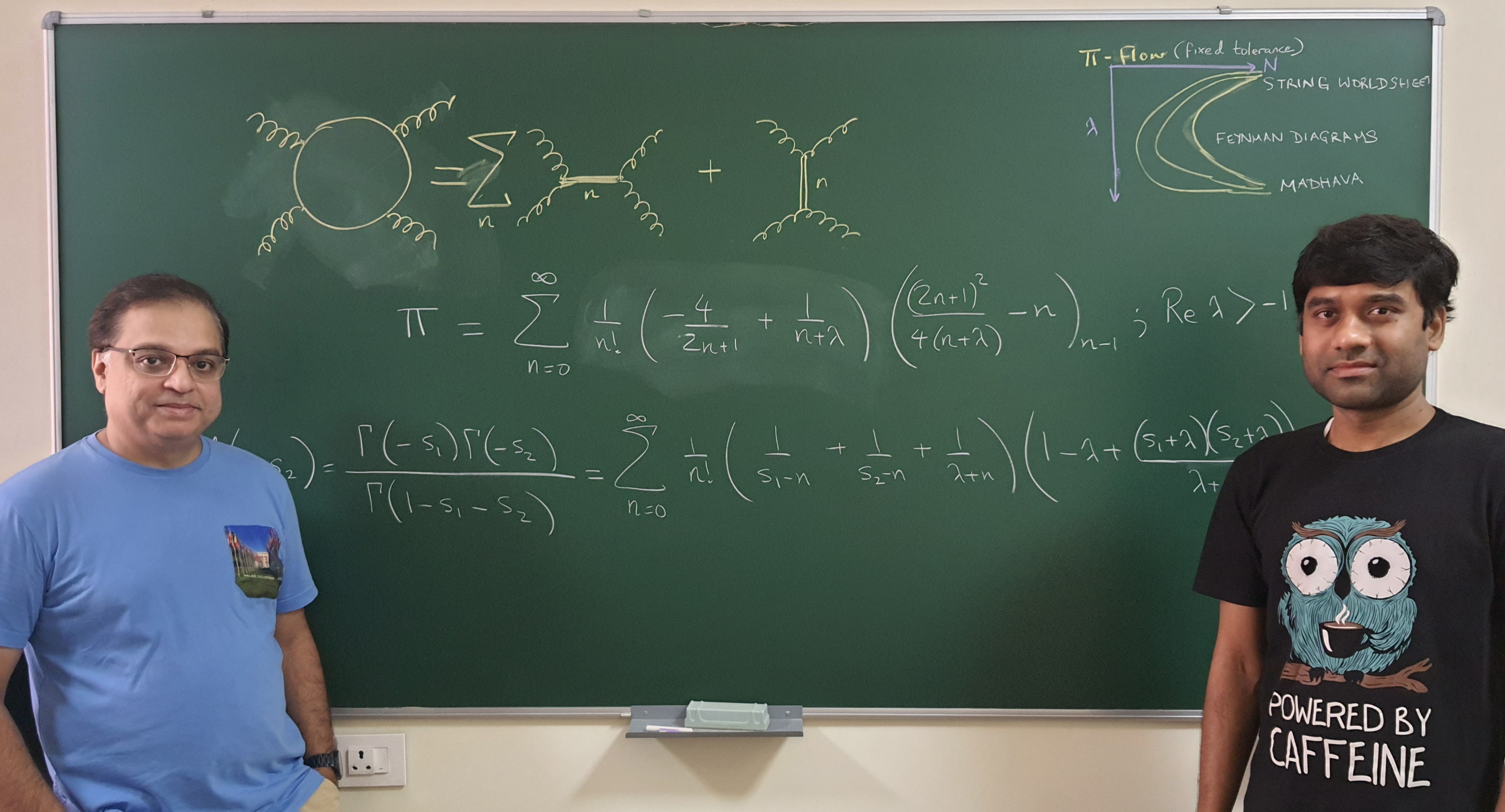

The new formula under a certain limit closely reaches the representation of pi suggested by Indian mathematician Sangamagrama Madhava in the 15th century, which was the first ever series for pi recorded in history. The study was carried out by Arnab Saha, a post-doc and Aninda Sinha, Professor at Centre for High Energy Physics (CHEP), and published in Physical Review Letters.

“Our efforts, initially, were never to find a way to look at pi. All we were doing was studying high-energy physics in quantum theory and trying to develop a model with fewer and more accurate parameters to understand how particles interact. We were excited when we got a new way to look at pi,” Sinha says.

Aninda Sinha (left) and Arnab Saha (right) (Photo: Manu Y)

Sinha’s group is interested in string theory – the theoretical framework that presumes that all quantum processes in nature simply use different modes of vibrations plucked on a string. Their work focuses on how high energy particles interact with each other – such as protons smashing together in the Large Hadron Collider – and in what ways we can look at them using as few and as simple factors as possible. This way of representing complex interactions belongs to the category of “optimisation problems.” Modelling such processes is not easy because there are several parameters that need to be taken into account for each moving particle – its mass, its vibrations, the degrees of freedom available for its movement, and so on.

Saha, who has been working on the optimisation problem, was looking for ways to efficiently represent these particle interactions. To develop an efficient model, he and Sinha decided to club two mathematical tools: the Euler-Beta Function and the Feynman Diagram. Euler-Beta functions are mathematical functions used to solve problems in diverse areas of physics and engineering, including machine learning. The Feynman Diagram is a mathematical representation that explains the energy exchange that happens while two particles interact and scatter.

What the team found was not only an efficient model that could explain particle interaction, but also a series representation of pi.

In mathematics, a series is used to represent a parameter such as pi in its component form. If pi is the “dish” then the series is the “recipe”. Pi can be represented as a combination of many numbers of parameters (or ingredients). Finding the correct number and combination of these parameters to reach close to the exact value of pi rapidly has been a challenge. The series that Sinha and Saha have stumbled upon combines specific parameters in such a way that scientists can rapidly arrive at the value of pi, which can then be incorporated in calculations, like those involved in deciphering scattering of high-energy particles.

“Physicists (and mathematicians) have missed this so far since they did not have the right tools, which were only found through work we have been doing with collaborators over the last three years or so,” Sinha explains. “In the early 1970s, scientists briefly examined this line of research but quickly abandoned it since it was too complicated.”

Although the findings are theoretical at this stage, it is not impossible that they may lead to practical applications in the future. Sinha points to how Paul Dirac worked on the mathematics of the motion and existence of electrons in 1928, but never thought that his findings would later provide clues to the discovery of the positron, and then to the design of Positron Emission Tomography (PET) used to scan the body for diseases and abnormalities. “Doing this kind of work, although it may not see an immediate application in daily life, gives the pure pleasure of doing theory for the sake of doing it,” Sinha adds.

REFERENCE:

Saha AP, Sinha A, Field theory expansions of string theory amplitudes, Physical Review Letters (2024).

CONTACT:

Aninda Sinha

Professor, Centre for High Energy Physics (CHEP)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: asinha@iisc.ac.in

Phone: +91-80-22932851

Website: https://chep.iisc.ac.in/Personnel/asinha.html

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

Novel strategy to make fast-charging solid-state batteries

2nd June 2022

– Ranjini Raghunath

In a breakthrough, researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) and their collaborators have discovered how next-generation solid-state batteries fail and devised a novel strategy to make these batteries last longer and charge faster.

Solid-state batteries are poised to replace the lithium-ion batteries found in almost every portable electronic device. But on repeated or excessive use, they develop thin filaments called ‘dendrites’ which can short-circuit the batteries and render them useless.

In a new study published in Nature Materials, the researchers have identified the root cause of this dendrite formation – the appearance of microscopic voids in one of the electrodes early on. They also show that adding a thin layer of certain metals to the electrolyte surface significantly delays dendrite formation, extending the battery’s life and enabling it to be charged faster.

Schematic (a) representing a Li-metal solid-state battery with a discontinuous interface. These voids and discontinuities are the main driving factor for dendrite growth through solid electrolytes. These voids can be minimised by using an appropriate interlayer (b) (Credit: Vikalp Raj)

Conventional lithium-ion batteries – the kind that you might find in your smartphone or laptop – contain a liquid electrolyte sandwiched between a positively charged electrode (cathode) made of a transition metal (such as iron and cobalt) oxide and a negatively charged electrode (anode) made of graphite. When the battery is charging and discharging (using up power), lithium ions shuttle between the anode and cathode in opposite directions. These batteries have a major safety issue – the liquid electrolyte can catch fire at high temperatures. Graphite also stores much less charge than metallic lithium.

A promising alternative, therefore, is solid-state batteries that switch out the liquid for a solid ceramic electrolyte and swap graphite with metallic lithium. Ceramic electrolytes perform even better at higher temperatures, which is especially useful in tropical countries like India. Lithium is also lighter and stores more charge than graphite, which can significantly cut down the battery cost.

“Unfortunately, when you add lithium, it forms these filaments that grow into the solid electrolyte, and short out the anode and cathode,” explains Naga Phani Aetukuri, Assistant Professor in the Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit (SSCU) and corresponding author of the study.

To investigate this phenomenon, Aetukuri’s PhD student, Vikalp Raj, artificially induced dendrite formation by repeatedly charging hundreds of battery cells, slicing out thin sections of the lithium-electrolyte interface, and peering at them under a scanning electron microscope. When they looked closely at these sections, the team realised that something was happening long before the dendrites formed – microscopic voids were developing in the lithium anode during discharge. The team also computed that the currents concentrated at the edges of these microscopic voids were about 10,000 times larger than the average currents across the battery cell, which was likely creating stress on the solid electrolyte and accelerating the dendrite formation.

“This means that now our task to make very good batteries is very simple,” says Aetukuri. “All that we need is to ensure that the voids don’t form.”

To ensure this, the researchers introduced an ultrathin layer of a refractory metal – a metal that is resistant to heat and wear – between the lithium anode and solid electrolyte. “The refractory metal layer shields the solid electrolyte from the stress and redistributes the current to an extent,” says Aetukuri. He and his team collaborated with researchers at Carnegie Mellon University in the US, who carried out computational analysis which clearly showed that the refractory metal layer indeed delayed the growth of microscopic lithium voids.

Advanced battery testing facility at IISc (Credit: Naga Phani Aetukuri)

Applying extreme pressure that can push lithium against the solid electrolyte can prevent voids and delay dendrite formation, but that may not be practical for everyday applications. Other researchers have also proposed the idea of using metals like aluminium that alloy or mix well with lithium at the interface. But over time, this metal layer blends with lithium, becoming indistinguishable, and does not prevent dendrite formation. “What we are saying is different,” explains Raj. “If you use a metal like tungsten or molybdenum that doesn’t alloy with lithium, the performance which you get from the cell is even better.”

The researchers say that the findings are a critical step forward in realising practical and commercial solid-state batteries. Their strategy can also be extended to other types of batteries that contain metals like sodium, zinc and magnesium.

REFERENCE:

Vikalp Raj, Victor Venturi, Varun R Kankanallu, Bibhatsu Kuiri, Venkatasubramanian Viswanathan and Naga Phani B Aetukuri, Direct Correlation Between Void Formation and Lithium Dendrite Growth in Solid State Electrolytes with Interlayers, Nature Materials (2022).

DOI: 10.1038/s41563-022-01264-8

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41563-022-01264-8

CONTACT:

Naga Phani Aetukuri

Assistant Professor

Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit (SSCU)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

phani@iisc.ac.in

+91-80-2293 3534

https://sites.google.com/view/qlab-iisc/home

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

- a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

- b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.inor pro@ac.in.

Miniproteins that can launch two-pronged attacks on viral proteins

4th June 2022

– Narmada Khare

The rapid emergence of new strains of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has diminished the protection offered by COVID-19 vaccines. A new approach developed by researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) now provides an alternative mechanism to render viruses like SARS-CoV-2 inactive.

In a study published in Nature Chemical Biology, the researchers report the design of a new class of artificial peptides or miniproteins that can not only block virus entry into our cells but also clump virions (virus particles) together, reducing their ability to infect.

A protein-protein interaction is often like that of a lock and a key. This interaction can be hampered by a lab-made miniprotein that mimics, competes with, and prevents the ‘key’ from binding to the ‘lock’, or vice versa.

In the new study, the team has exploited this approach to design miniproteins that can bind to, and block the spike protein on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This binding was further characterised extensively by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and other biophysical methods.

These miniproteins are helical, hairpin-shaped peptides, each capable of pairing up with another of its kind, forming what is known as a dimer. Each dimeric ‘bundle’ presents two ‘faces’ to interact with two target molecules. The researchers hypothesised that the two faces would bind to two separate target proteins locking all four in a complex and blocking the targets’ action. “But we needed proof of principle,” says Jayanta Chatterjee, Associate Professor in the Molecular Biophysics Unit (MBU), IISc, and the lead author of the study. The team decided to test their hypothesis by using one of the miniproteins called SIH-5 to target the interaction between the Spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 protein in human cells.

The S protein is a trimer – a complex of three identical polypeptides. Each polypeptide contains a Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) that binds to the ACE2 receptor on the host cell surface. This interaction facilitates viral entry into the cell.

The SIH-5 miniprotein was designed to block the binding of the RBD to human ACE2. When a SIH-5 dimer encountered an S protein, one of its faces bound tightly to one of the three RBDs on the S protein trimer, and the other face bound to an RBD from a different S protein. This ‘cross-linking’ allowed the miniprotein to block both S proteins at the same time. “Several monomers can block their targets,” says Chatterjee. “[But] cross-linking of S proteins blocks their action many times more effectively. This is called the avidity effect.”

Dimerisation of spike protein by ‘two-faced peptide’ (Credit: Bhavesh Khatri)

Under cryo-EM, the S proteins targeted by SIH-5 appeared to be attached head-to-head. “We expected to see a complex of one spike trimer with SIH-5 peptides. But I saw a structure that was much more elongated,” says Somnath Dutta, Assistant Professor at MBU and one of the corresponding authors. Dutta and the others realised that the spike proteins were being forced to form dimers and clumped into complexes with the miniprotein. This type of clumping can simultaneously inactivate multiple spike proteins of the same virus and even multiple virus particles. “I have worked with antibodies raised against the spike protein before and observed them under a cryo-EM. But they never created dimers of the spikes,” says Dutta.

The miniprotein was also found to be thermostable – it can be stored for months at room temperature without deteriorating.

The next step was to ask if SIH-5 would be useful for preventing COVID-19 infection.

To answer this, the team first tested the miniprotein for toxicity in mammalian cells in the lab and found it to be safe. Next, in experiments carried out in the lab of Raghavan Varadarajan, Professor at MBU, hamsters were dosed with the miniprotein, followed by exposure to SARS-CoV-2. These animals showed no weight loss and had greatly decreased viral load as well as much less cell damage in the lungs, compared to hamsters exposed only to the virus.

The researchers believe that with minor modifications and peptide engineering, this lab-made miniprotein could inhibit other protein-protein interactions as well.

REFERENCE:

Khatri B, Pramanick I, Malladi SK, Rajmani RS, Kumar S, Ghosh P, Sengupta N, Rahisuddin R, Kumar N, Kumaran S, Ringe RP, Varadarajan R, Dutta S, Chatterjee J, A dimeric proteomimetic prevents SARS-CoV-2 infection by dimerizing the spike protein, Nature Chemical Biology (2022).

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41589-022-01060-0

CONTACT:

Jayanta Chatterjee

Associate Professor

Molecular Biophysics Unit (MBU)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

jayanta@iisc.ac.in

080-2293 2053

Somnath Dutta

Assistant Professor

Molecular Biophysics Unit (MBU)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

somnath@iisc.ac.in

080-2293 3453

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release. b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

‘Snapping’ footwear to help prevent diabetic foot complications

13th June 2022

– Mohammed Asheruddin

Researchers in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Indian Institute of Science (IISc), in collaboration with the Karnataka Institute of Endocrinology and Research (KIER), have developed a set of unique self-regulating footwear for persons with diabetes.

Foot injuries or wounds in persons with diabetes heal at a slower rate than in healthy individuals, which increases the chance of infection, and may lead to complications that require amputation in extreme cases.

The footwear – a pair of specially-designed sandals – developed by the IISc-led team is 3D printed and can be customised to an individual’s foot dimensions and walking style. Unlike conventional therapeutic footwear, a snapping mechanism in these sandals keeps the feet well-balanced, enabling faster healing of the injured region and preventing injuries from arising in other areas of the feet.

Footwear with self-offloading insole underneath the top sole (b) one of the volunteers wearing the self-offloading footwear (Credit: Priyabrata Maharana, Jyoti Sonawane)

The footwear can be especially beneficial for people who have diabetic peripheral neuropathy – those who suffer from nerve damage caused by diabetes, leading to a loss of sensation in the foot. “Diabetic peripheral neuropathy is one of the long-term complications of diabetes, and its diagnosis is mostly neglected,” says Pavan Belehalli, Head of the Department of Podiatry at KIER, and one of the authors of the study published in Wearable Technologies. This loss of sensation leads to irregular walking patterns in persons with diabetes, he says.

For example, a healthy person usually places their heel first on the ground, followed by the foot and toes, and then the heel again – this ‘gait cycle’ distributes the pressure evenly across the foot. But due to the loss of sensation, persons with diabetes may not always follow this sequence, which means that the pressure is unevenly distributed. Regions of the foot where the pressure exerted is high are at greater risk of developing ulcers, corns, calluses and other complications.

Most of the therapeutic footwear available in the market is ineffective at off-loading the uneven pressure exerted by the ‘abnormal’ gait cycle of persons with diabetes, the researchers say. To address this challenge, they designed arches in their sandals that ‘snap’ to an inverted shape when a pressure beyond a certain threshold is applied. “When we remove the pressure, [the arch] will automatically come back to its initial position – this is what is called self-offloading,” explains first author Priyabrata Maharana, PhD student in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, IISc. “We consider the individual’s weight, foot size, walking speed and pressure distribution to arrive at the maximum force that has to be off-loaded.” Multiple arches have been designed along the length of the footwear to off-load the pressure effectively.

3D-printed prototype of self-offloading insole showing the arrangement of array of arches ((a) top view and (b) side view) to offload the high-pressure areas (Credit: Priyabrata Maharana, Jyoti Sonawane)

“This is a mechanical solution to a problem,” explains GK Ananthasuresh, Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, IISc, and senior author of the study. “Most of the time, people use electromechanical solutions.” Such solutions involve using sensors and actuators that can rack up the price of the footwear and make them very expensive, he adds.

The team is collaborating with start-ups Foot Secure and Yostra Labs to commercialise their product. “There are a lot of commercial shoe manufacturers selling costly footwear in the name of giving comfort using what they call memory foam, but we have tested them, and they don’t have the required characteristics,” says Ananthasuresh. “This footwear can be used not only by people suffering from diabetic neuropathy, but by others as well.”

REFERENCE:

Maharana P, Sonawane J, Belehalli P, Ananthasuresh GK, Self-offloading therapeutic footwear using compliant snap-through arches, Wearable Technologies (2022).

CONTACT:

G K Ananthasuresh

Professor

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: suresh@iisc.ac.in

Telephone: +91 (80) 2293 2334

Pavan Belehalli

Head of Department

Department of Podiatry

Karnataka Institute of Endocrinology and Research (KIER)

Email: docbelehalli@gmail.com

Priyabrata Maharana

PhD student

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Indian Institute of Science

Email:<priyabratam@iisc.ac.in

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

Studying COVID-19 spread during short conversations

17th June 2022

– Pratibha Gopalakrishna

When a person sneezes or coughs, they can potentially transmit droplets carrying viruses like SARS-CoV-2 to others in their vicinity. Does talking to an infected person also carry an increased risk of infection? How do speech droplets or “aerosols” move in the air space between the people interacting?

To answer these questions, a research team has carried out computer simulations to analyse the movement of the speech aerosols. The team includes researchers from the Department of Aerospace Engineering, Indian Institute of Science (IISc), along with collaborators from the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics (NORDITA) in Stockholm and the International Centre for Theoretical Sciences (ICTS) in Bengaluru. Their study was published in the journal Flow.

The team visualised scenarios in which two maskless people are standing two, four or six feet apart and talking to each other for about a minute, and then estimated the rate and extent of spread of the speech aerosols from one to another. Their simulations showed that the risk of getting infected was higher when one person acted as a passive listener and didn’t engage in a two-way conversation. Factors like the height difference between the people talking and the quantity of aerosols released from their mouths also appear to play an important role in viral transmission.

“Speaking is a complex activity … and when people speak, they’re not really conscious of whether this can constitute a means of virus transmission,” says Sourabh Diwan, Assistant Professor in the Department of Aerospace Engineering, and one of the corresponding authors.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts believed that the virus mostly spread symptomatically through coughing or sneezing. Soon, it became clear that asymptomatic transmission also leads to the spread of COVID-19. However, very few studies have looked at aerosol transport by speech as a possible mode of asymptomatic transmission, according to Diwan.

To analyse speech flows, he and his team modified a computer code they had originally developed to study the movement and behaviour of cumulus clouds – the puffy cotton-like clouds that are usually seen on a sunny day. The code (called Megha-5) was written by S Ravichandran from NORDITA, the other corresponding author on the paper, and was used recently for studying particle-flow interaction in Rama Govindarajan’s group at ICTS. The analysis carried out by the team on speech flows incorporated the possibility of viral entry through the eyes and mouth in determining the risk of infection – most previous studies had only considered the nose as the point of entry.

Interactions of speech jets during short conversations between two people separated by a distance of four feet, visualised by an iso-surface of the aerosol concentration. Three different height differences are shown. The blue and red colours represent the simulated speech jets emanating from the mouths of the two people. The simulations were performed on SahasraT at IISc (Image: Rohit Singhal)

“The computational part was intensive, and it took a lot of time to perform these simulations,” explains Rohit Singhal, first author and PhD student at the Department of Aerospace Engineering. Diwan adds that it is hard to numerically simulate the flow of speech aerosols because of the highly-fluctuating (“turbulent”) nature of the flow; factors like the flow rate at the mouth and the duration of speech also play a role in shaping its evolution.

In the simulations, when the speakers were either of the same height, or of drastically different heights (one tall and another short), the risk of infection was found to be much lower than when the height difference was moderate – the variation looked like a bell curve. Based on their results, the team suggests that just turning their heads away by about nine degrees from each other while still maintaining eye contact can reduce the risk for the speakers considerably.

Moving forward, the team plans to focus on simulating differences in the loudness of the speakers’ voices and the presence of ventilation sources in their vicinity to see what effect they can have on viral transmission. They also plan to engage in discussions with public health policymakers and epidemiologists to develop suitable guidelines. “Whatever precautions we can take while we come back to normalcy in our daily interactions with other people, would go a long way in minimising the spread of infection,” Diwan says.

REFERENCE:

Singhal R, Ravichandran S, Govindarajan R, and Diwan S, Virus transmission by aerosol transport during short conversations, Flow, 2 (2022): E13. doi:10.1017/flo.2022.7.

CONTACT:

Sourabh S Diwan

Assistant Professor

Department of Aerospace Engineering

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: sdiwan@iisc.ac.in

Phone: +91-80-22932423

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

a) If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

b) For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.in or pro@iisc.ac.in.

Using GPUs to discover human brain connectivity

27th June 2022

– Praveen Jayakumar

A new GPU-based machine learning algorithm developed by researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) can help scientists better understand and predict connectivity between different regions of the brain.

The algorithm, called Regularized, Accelerated, Linear Fascicle Evaluation, or ReAl-LiFE, can rapidly analyse the enormous amounts of data generated from diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging (dMRI) scans of the human brain. Using ReAL-LiFE, the team was able to evaluate dMRI data over 150 times faster than existing state-of-the-art algorithms.

“Tasks that previously took hours to days can be completed within seconds to minutes,” says Devarajan Sridharan, Associate Professor at the Centre for Neuroscience (CNS), IISc, and corresponding author of the study published in the journal Nature Computational Science.

The image shows the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), a white matter tract that connects the prefrontal and parietal cortex, two attention-related brain regions. The tract was estimated with diffusion MRI and tractography in the living human brain (Credits: Varsha Sreenivasan and Devarajan Sridharan)

Millions of neurons fire in the brain every second, generating electrical pulses that travel across neuronal networks from one point in the brain to another through connecting cables or “axons”. These connections are essential for computations that the brain performs. “Understanding brain connectivity is critical for uncovering brain-behaviour relationships at scale,” says Varsha Sreenivasan, PhD student at CNS and first author of the study. However, conventional approaches to study brain connectivity typically use animal models, and are invasive. dMRI scans, on the other hand, provide a non-invasive method to study brain connectivity in humans.

The cables (axons) that connect different areas of the brain are its information highways. Because bundles of axons are shaped like tubes, water molecules move through them, along their length, in a directed manner. dMRI allows scientists to track this movement, in order to create a comprehensive map of the network of fibres across the brain, called a connectome.

Unfortunately, it is not straightforward to pinpoint these connectomes. The data obtained from the scans only provide the net flow of water molecules at each point in the brain. “Imagine that the water molecules are cars. The obtained information is the direction and speed of the vehicles at each point in space and time with no information about the roads. Our task is similar to inferring the networks of roads by observing these traffic patterns,” explains Sridharan.

The image shows connections between the midbrain and various regions of the neocortex. Connections to each region are shown in a different colour, and were all estimated with diffusion MRI and tractography in the living human brain (Credits: Varsha Sreenivasan and Devarajan Sridharan)

To identify these networks accurately, conventional algorithms closely match the predicted dMRI signal from the inferred connectome with the observed dMRI signal. Scientists had previously developed an algorithm called LiFE (Linear Fascicle Evaluation) to carry out this optimisation, but one of its challenges was that it worked on traditional Central Processing Units (CPUs), which made the computation time-consuming.

In the new study, Sridharan’s team tweaked their algorithm to cut down the computational effort involved in several ways, including removing redundant connections, thereby improving upon LiFE’s performance significantly. To speed up the algorithm further, the team also redesigned it to work on specialised electronic chips – the kind found in high-end gaming computers – called Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), which helped them analyse data at speeds 100-150 times faster than previous approaches.

This improved algorithm, ReAl-LiFE, was also able to predict how a human test subject would behave or carry out a specific task. In other words, using the connection strengths estimated by the algorithm for each individual, the team was able to explain variations in behavioural and cognitive test scores across a group of 200 participants.

Such analysis can have medical applications too. “Data processing on large scales is becoming increasingly necessary for big-data neuroscience applications, especially for understanding healthy brain function and brain pathology,” says Sreenivasan.

For example, using the obtained connectomes, the team hopes to be able to identify early signs of aging or deterioration of brain function before they manifest behaviourally in Alzheimer’s patients. “In another study, we found that a previous version of ReAL-LiFE could do better than other competing algorithms for distinguishing patients with Alzheimer’s disease from healthy controls,” says Sridharan. He adds that their GPU-based implementation is very general, and can be used to tackle optimisation problems in many other fields as well.

REFERENCE:

Sreenivasan V, Kumar S, Pestilli F, Talukdar P, Sridharan D, GPU-accelerated connectome discovery at scale. Nature Computational Science 2, 298–306 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-022-00250-z

The research was supported by the DBT Wellcome Trust India Alliance, among other funding agencies.

CONTACT:

Devarajan Sridharan

Associate Professor, Centre for Neuroscience (CNS)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: sridhar@iisc.ac.in

Phone: +91-80-22933434

Varsha Sreenivasan

PhD student, Centre for Neuroscience (CNS)

Indian Institute of Science (IISc)

Email: varshas@iisc.ac.in

NOTE TO JOURNALISTS:

- If any of the text in this release is reproduced verbatim, please credit the IISc press release.

- For any queries about IISc press releases, please write to news@iisc.ac.inor pro@iisc.ac.in.

Pagination

- Page 1

- Next page